Marcus Coates

LONDON

at Workplace

The subject of animals and the natural world has become a major curatorial trend in the United Kingdom in recent years, and no British artist is situated more centrally within that discourse than Marcus Coates, whose work appears in most zoologically themed shows. Coates is the go-to guy for injecting a certain tone of irony and bathos, most notably with the quasi-shamanic projects where he adopts the guise of animals—the point being that his costumes and behaviors are less about truly emulating or understanding animals than about channeling human desires.

His most recent body of work stems from a period he spent on Fogo Island in Newfoundland, and sees him shifting toward broader ecological concerns. The video Apology to the Great Auk (2017) is based on one of the most notorious episodes in natural history: the hunting to extinction, by the middle of the nineteenth century, of the North Atlantic bird species the great auk, which was prized for its soft down. The piece cuts between three different scenes: Coates meeting with the island’s mayor to get a formal statement of apology ratified; Coates chairing a committee of islanders to debate the language the document should be couched in; and the mayor publicly reading aloud the final draft, addressing the vanished birds themselves through a loudspeaker aimed out to sea. “Your extinction is a defining moment in the history of the world,” he intones, promising “to do all we can to protect the other auks, the birds and animals we share our territory with.” Yet for all the apparent sincerity of the message, the inherent absurdism of the proceedings is also palpable—the idea that any bureaucratic or oratorical act might compensate for the destruction of a species. Ultimately, the symbolic address to all of great auk–dom comes off as simply a form of anthropomorphism, as another way of ascribing value to animals based on human utility, in this case their capacity to serve as vehicles for off-loading the guilt we feel at our environmental depredations. The video’s shots of the empty, endless sea seem to imply the apology is equally a sort of empty gesture. Still, it’s a shame that Coates didn’t see fit to delve more into the historical background, the European colonization that formed the conditions for ecological exploitation.

A companion video, The Last of Its Kind (2017), was also shot on Fogo Island. This time, it is Coates who serves as representative of a species, acting the role, in some unspecified future scenario, of the final human being alive in the world. Shouting out to sea, standing naked behind a deserted stone ruin on the rocky coastline, he boasts about humanity’s achievements, listing the marvels of civilization—everything from the Bible and the Koran to Shakespeare to radios and refrigerators to feminism. Like a sort of litany or mantra, the list gets repeated numerous times, his declamations becoming increasingly fraught and desperate, swallowed up by the encompassing vastness of sky and ocean. Yet somehow the work never feels as tragic, or as tragicomic, as it was presumably intended. The problem, essentially, is its reliance on the overfamiliar Romantic trope of sublime, indifferent nature. Coates’s work is better when it seeks instead to deconstruct our received ideas of the natural world.

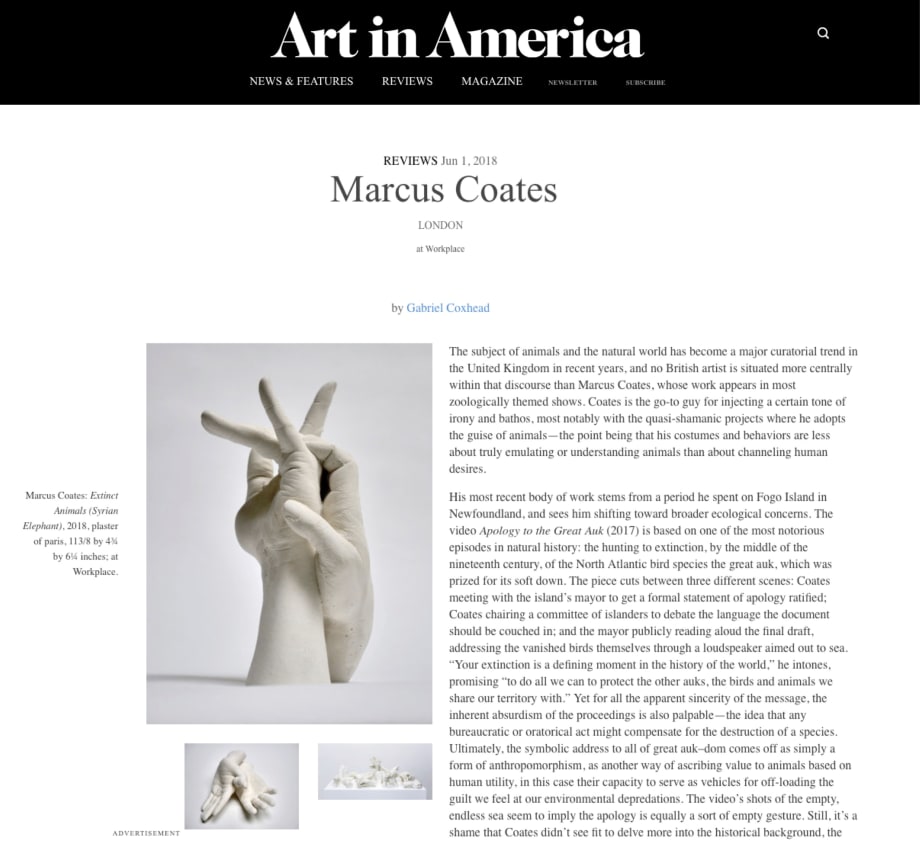

In that sense, his sculpture series “Extinct Animals” (2018) feels more astute. The works comprise plaster casts of hands posed in the sort of gestures one would make to cast animal-shaped shadows. Several species—the Syrian elephant, for instance, and the passenger pigeon—are ably portrayed. But others, such as the Yangtze River dolphin, required fingers to be lopped off to create the right shapes. The Lake Pedder earthworm is represented by a single, amputated digit. The sense is of the shortcomings of humanity; and of nature refusing to conform to our easy, self-centered representations of it.

By Gabriel Coxhead